- Home

- Carmela Ciuraru

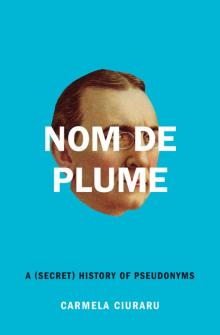

Nom de Plume Page 5

Nom de Plume Read online

Page 5

And faith shines equal, arming me from Fear.

The Brontë sisters had aggressively offended, challenged, and violated Victorian morals with their revolutionary works, which were profoundly disturbing for their era. In concealing their true identities, the Brontës could speak the truth without facing judgment. By overturning rigid societal notions of a distinctly “male” or “female” imagination, they raised provocative questions about the nature of creativity.

“If men could see us as we really are,” Charlotte once wrote, “they would be amazed.”

She was a bisexual, cigar-smoking cross-dresser

Chapter 2

George Sand & AURORE DUPIN

It began with an ankle-length gray military coat, matching trousers, a cravat, and a waistcoat. Clothes may make the man, as Mark Twain famously noted, but in this instance, they made the woman the man.

She was born Amandine-Aurore-Lucile Dupin in Paris in the summer of 1804, shortly before Napoleon became emperor of France. She was known as Aurore. “My father was playing the violin and my mother wore a pretty pink dress,” she would report of her birth in her epic, two-volume memoir, Histoire de ma vie. “It took but a minute.” Her parents had married secretly weeks before, making their daughter legitimate. In later years Aurore claimed to have walked at ten months, and to have been an adept reader by age four. “My looks gave promise of great beauty, a promise unkept,” she recalled, with no trace of regret. “This was perhaps my own fault, because at the age when beauty blossoms, I was already spending my nights reading and writing.”

Even in childhood Aurore was unconventional, finding delight and power in her own precociousness. She was an explorer, constantly testing boundaries in her behavior and pushing back at authority figures. Though her mother valued beauty above all, Aurore deplored the notion of “living under a bell jar so as to avoid being weather-beaten, chapped, or faded before your time.” She shunned hats and gloves and lessons in becoming a proper young lady. Gestures of reticence and grace were of no interest. She didn’t rebel for the sake of rebellion, but “I could not be coerced.” She daydreamed endlessly, befriended boys and girls alike, and cultivated a certain wildness of intellect and character. Already she displayed hints of the adult she would become, magnanimous and brave.

Aurore’s identity evolved largely in opposition to her mother’s character. Yet in one regard, her mother unwittingly exerted a profound influence. A former stage actress and prostitute, Antoinette Sophie-Victoire Delaborde Dupin had a lifelong tendency toward melodrama and instability—thus teaching Aurore that selves could be cycled through and discarded at will. Aurore’s mother was raised in poverty, the daughter of a bird seller; her husband was descended from a family of aristocrats. (Both had illegitimate children from previous relationships—he had a son, Hippolyte; she had a daughter, Caroline.) The class schism was a source of tension in their relationship, and would become a recurring theme in Aurore’s fiction. Antoinette’s mother-in-law came to accept, and even adore, Aurore but could not endorse her son’s marriage, which she deemed “disproportionate,” and she considered his wife contemptible. The best state the two women would ever settle into was a kind of benign antipathy.

Over the years the mercurial Antoinette preferred to be called Victoire, and then, after her marriage, Sophie. At times she had only a tenuous grip on reality, and this condition worsened as she aged. She was impulsive and manipulative. Roles and selves were interchanged to suit her circumstances. “When she was in good spirits,” Aurore recalled of her mother, “she was truly charming, and it was impossible not to be swept up in her buoyant gaiety and vivid witticisms. Unfortunately, it would never last an entire day; lightning would strike from some remote corner of heaven.”

At least one thing kept the mother-daughter relationship close: the art of storytelling. As a girl, Aurore delighted in hearing her mother read stories and sing lullabies to her. She loved the sounds of words, developed a rich imagination, and became a compulsive storyteller herself. “I used to compose out loud interminably long tales which my mother used to call my novels,” she later recalled.

She had a knack for embellishment, or perhaps a dubious memory (though she once dismissed forgetfulness as unintelligence or inattention). In her autobiography, Aurore shared what she claimed was the first memory of her life, an incident that occurred when she was two years old and that she recalled in remarkable detail:

A servant let me fall out of her arms onto the corner of the fireplace; I was frightened, and I hurt my forehead. All the commotion, the shock to the nervous system opened me to self-awareness, and I saw clearly—I still see—the reddish marble of the mantelpiece, my blood running, the distraught face of my nursemaid. I distinctly remember the doctor who came, the leeches which were put behind my ears, my mother’s anxiety, and the servant dismissed for drunkenness.

Was this recollection accurate in every, or even any, aspect? Did the incident happen at all? No matter. Aurore cast her younger self at the center of a drama vividly told. She was both subject and object. She also claimed to remember perfectly the apartment her family lived in a year later, on Rue Grange-Batalière, and she said that from then on, “my memories are precise and nearly without interruption.” It’s an astonishing claim, regardless of how attentive young Aurore must have been to the world around her.

Since her mother was often unavailable physically and emotionally, Aurore spent countless hours in solitude. She craved touch. When she wasn’t telling stories to her rapt listener, a pet rabbit, she was beginning to discover the thrills of playing with different personae. The first time she called out into the empty flat and heard her own voice call back the same words, she recalled thinking, “I was double and somewhere nearby was another ‘me’ whom I could not see but who always saw me since it always answered me.” She didn’t realize that it was only the echo of her own voice calling back until her mother later told her this, but the idea of “doubleness” had been planted, and it delighted her. She gave the voice a name and would call out, “Echo, are you there? Do you hear me? Hello, echo!”

Although Sophie’s husband, Maurice Dupin, a military officer, was rarely present, his letters home showed how much he loved his family: “How dear is our Aurore!” he wrote in September 1805, two days before the Battle of Austerlitz. “How impatient you make me to come back and take both of you into my arms! . . . Tell me about your love, our child. Know that you’d destroy my life if you should cease to love me. Know that you’re my wife, that I adore you, that I love life only because of you, and that I’ve dedicated my life to you.” Elsewhere he implored, “May you always feel gloomy in my absence. Yes, beloved wife, that is how I love you. Let no one see you, think only of taking care of our daughter, and I’ll be happy as I can be far from you.”

Sophie seemed to take his words to heart. In her husband’s absence, the Dupin house, with only mother and daughter, was lonely and listless. (The illegitimate children mostly lived elsewhere, though Hippolyte would become quite close to his half sister Aurore.) Maurice’s periodic returns invigorated their lives, at least temporarily. “[My parents] found themselves happy only in their little household,” Aurore would later recall. “Everywhere else they suffocated from melancholy yawning, and they left me with this legacy of secret savagery, which has always made society intolerable for me and ‘the home’ a necessity.”

In the autumn of 1808, Maurice was thrown from his horse, Leopardo, and instantly killed. He was thirty. Just eight days earlier, he and Sophie had suffered the devastating loss of their infant son, Louis. After Maurice died, Aurore saw her mother crying one day and shyly approached her. “But when my daddy is through being dead,” she said, “he’ll come back to see you, won’t he?”

She recalled that the house was “plunged into melancholy.” Sophie’s fragile, shifting self may have been a means of resilience against the hardships she suffered.

But whatever the cause, her condition worsened after the deaths of Maurice and Louis, and her perpetual instability provided a template for Aurore’s own ideas about identity: “It seems to me that we change from day to day and that after some years we are a new being,” she reflected late in life. This notion was liberating—Aurore was a fearless risk-taker, rushing headlong into new experiences—but it also had a grievous effect, leaving her with a lifelong pining for love and intimacy that, occasional salves aside, would never be filled.

Following the losses of her brother and father, Aurore’s love of daydreaming and storytelling became obsessive; imagination was no longer merely a retreat from boredom and solitude but a life raft, a need. “She’s not trying to be difficult; it’s her nature,” her mother would explain. “You may be sure that she’s always meditating on something. She used to chatter when she daydreamed.” Aurore never relinquished her belief in the virtues of clinging to the imagination: “To cut short the fantasy life of a child is to go against the very laws of nature,” she wrote.

Her grandmother was increasingly troubled by her peculiar behavior, and in 1817 Madame Dupin decided to rectify it by sending the thirteen-year-old to a convent, Couvent des Anglaises, in Paris. Aurore later recounted her grandmother’s harsh assessment of her at the time: “You have inherited an excellent intelligence from your father and grandparents, but you do all in your power to appear an idiot. You could be attractive, but you take pride in looking unkempt. . . . You have no bearing, no grace, no tact. Your mind is becoming as deformed as your body. Sometimes you hardly reply when spoken to, and you assume the air of a bold animal that scorns human contact. . . . It is time to change all this.”

At the convent, Aurore alternated between subversive behavior (“Let me say in passing that the great fault of monastic education is the attempt to exaggerate chastity,” she later wrote), and austere withdrawal. Despite the excessive instruction, she admitted, “I still slouched, moved too abruptly, walked too naturally, and could not bear the thought of gloves or deep curtsies.” Aurore said that when her grandmother would scold her for these “vices,” “it took great self-control for me to hide the annoyance and irritation these eternal little critiques caused me. I would so like to have pleased her! I was never able to.” Aurore could not (and had no wish to) shake off her propensity for daydreaming—“my mind, sluggish and wrapped up in itself, was still that of a child.” She wrote poems at the convent, and even completed two novels; the second was “a pastoral one, which I judged worse than my first and with which I lit the stove one winter’s day.”

During this period, her grandmother exerted tremendous control over Aurore’s education and development. (She accomplished this by threatening to disinherit Aurore.) Dying, Madame Dupin was concerned, as ever, about what she saw as the toxic effects of Sophie’s influence on her granddaughter. She was determined to instill in Aurore moral and intellectual development; a socially acceptable degree of independence; a permanent distrust of Sophie and her family; and to remove Aurore from a “lower-class environment” into established society—which also meant finding a proper husband.

As a result, Sophie gave up custody of Aurore for a time. “It seemed as though she was ready to accept for herself a future in which I was no longer an essential party,” Aurore wrote of her mother. Resigned to Madame Dupin’s authority and dominance, Sophie would not engage in a contest of wills with her mother-in-law. The distance between mother and daughter was painful. “My mother seemed to have abandoned me to my silent and miserable struggle,” Aurore recalled. “I was desolate over her apparent abandonment of me after the passion she had showered on me in my childhood.” Maternal nurturing was provided instead by a nun, Sister Alicia, the first woman for whom Aurore had powerful feelings of love. In later years, with other women, Aurore would find physical intimacy, great passion, and much torment.

She left the convent in 1820, at age sixteen; within two years, she was married. It was the result of an extensive contractual agreement, following lengthy negotiations and financial haggling between the families. Her husband, Casimir Dudevant, the son of a baron, was a handsome twenty-seven-year-old sublieutenant in the French army. Sophie never warmed to him, explaining her dislike by saying that his nose didn’t please her. But Aurore found him an agreeable and reasonable companion, if not an ideal romantic suitor: “He never spoke to me of love, he admitted to being little disposed to sudden passion, or enthusiasm, and in any case, was incapable of expressing these sentiments in a seductive manner,” she recalled.

Nonetheless, by the spring of 1823 her first child was on the way: a son, Maurice, named for her father. And she already had stirrings of doubt about her marriage. Self-abnegation did not suit Aurore, who recognized it as an essential but unpleasant aspect of her union. “In marrying, one of the two must renounce himself or herself completely,” she noted. “All that remains to be asked, then, is whether it should be for the husband or the wife to recast his or her being according to the mould of the other.” On a family trip to the Pyrenees on her twenty-first birthday, she wrote in her diary: “I have to get used to smiling though my soul feels dead.”

Despite periods of depression, she delighted in motherhood and gave birth to a daughter, Solange, in the fall of 1828. Aurore was dissatisfied with her marriage intellectually, emotionally, and sexually. It was a functioning partnership, nothing more. She was slowly recasting herself, but hardly as the dutiful wife—though she had genuinely tried: “I made enormous efforts to see things through my husband’s eyes and think and do as he wished,” she later wrote. “But the minute I had come to agree with him, I would fall into dreadful sadness, because I no longer felt in agreement with my own instincts.”

The headstrong young woman was keenly interested in exploring other, more flamboyant and expansive roles. Just a year before she married, Aurore had made her first public appearance in a male disguise. She’d been riding her horse, Colette, one day, dressed in equestrian clothes, and was mistaken for a man. In a nearby village, she’d been addressed as “monsieur” by a woman, who had blushed and narrowed her eyes in “his” presence. Aurore was thrilled about her cross-dressing experiment and delighted by her own power. The illicit erotic charge wasn’t bad, either.

Although she was certainly adjusting to the mold of another, her new form did not belong to the dull Casimir but to George Sand, her literary persona, who would become France’s best-selling writer and would be among its most prolific authors. In considering what Sand accomplished, and the inspiring way she went about it, a dictum from the inimitable artist Louise Bourgeois comes to mind: “A woman has no place in the art world unless she proves over and over again she won’t be eliminated.”

Both Aurore and Casimir had casual affairs during their marriage, but at twenty-six, Aurore met a young Parisian who would play an important role in her life. When they fell in love, Jules Sandeau was nineteen and, like her, a writer. The first syllable of his surname (Sand) would become the surname of her pseudonym. Though their love affair didn’t last long, Sandeau proved enormously influential and helped her find her path toward a wholly independent life. “Inspiration can pass through the soul just as easily in the midst of an orgy as in the silence of the woods,” she wrote in her autobiography, “but when it is a question of giving form to your thoughts, whether you are secluded in your study or performing on the planks of a stage, you must be in total possession of yourself.” By 1830, she was well on her way.

The following year, she decided to assert her will rather forcefully. She told Casimir that she would live in Paris for half the year with Solange, returning in the other months to care for Maurice. Yet she went through many periods of replicating her own mother’s treatment of her—abandoning both children for long (and damaging) stretches to caretakers and tutors, in the single-minded pursuit of her own desires and ambitions. She wrestled with this but did not always remedy the situation to her children’s liking.

&

nbsp; Aurore’s loneliness in Paris, at first, was “profound and complete.” She felt useless. There was no doubt in her mind that literature alone “offered me the most chance of success as a profession.” The few people she confided in about it were skeptical that writing and monetary concerns could successfully coexist—at least for a woman.

She dabbled in other, more pragmatic attempts at work. Feeling despair over not being able to help the poor in any meaningful way, she became “a bit of a pharmacist,” preparing ointments and syrups for her clients gratis. She tried translation work, but because she was meticulous and conscientious with the words of others, it took too long. In attempting pencil and watercolor portraits done at sittings, she said, “I caught the likenesses very well, my little heads were not drawn badly, but the métier lacked distinction.” She tried sewing, and was quick at it, but it didn’t bring in much money and she couldn’t see well enough close up. In another profitless venture, she sold tea chests and cigar boxes she’d varnished and painted with ornamental birds and flowers. “For four years, I went along groping, or slaving at nothing worthwhile, in order to discover within me any capability whatsoever,” she recalled. “In spite of myself, I felt that I was an artist, without ever having dreamed I could be one.”

Jules Sandeau would play an integral role in her becoming a “public” writer, as she had already written prolifically in private. He was part of a bohemian circle that Aurore eagerly joined, one that provided stimulating political, artistic, and intellectual discourse. These were people she felt an affinity with (as she most certainly did not with her husband), and they would become her close friends. It was an exciting time, and she took full advantage, throwing herself passionately into the affair with Sandeau.

The tricky issue of financial independence lingered. In the winter of 1831, Aurore reluctantly arranged an interview, through an acquaintance, with the publisher of Le Figaro, Henri de Latouche. She cringed at the thought of newspaper work, but recognized it as a useful entry point to literary endeavors. Also, she appreciated Latouche’s intensity and fervent antibourgeois sensibility. He offered Aurore a job as columnist—making her the only woman on the staff and paying her seven francs per column. She was more than willing to prove herself. “I don’t believe in all the sorrows that people predict for me in the literary career on which I’m trying to embark,” she wrote in a letter to a friend. But when she called on an author to seek advice about the Parisian publishing world, the meeting was a disaster: “I shall be very brief, and I shall tell you frankly—a woman shouldn’t write,” he said before showing her the door. She recalled in her autobiography that because she left quietly, “prone more to laughter than anger,” he ended his harangue on the inferiority of women with “a Napoleonic stroke that was intended to crush me: ‘Take my word for it,’ he said gravely, as I was opening the outer door to his sanctum, ‘don’t make books, make babies!’”

Nom de Plume

Nom de Plume